Check out the Sault/Algoma Grow Me Instead Guide

for a list of the most locally concerning invasives as well as native alternatives

“What is an invasive plant?”

One that:

- Is not native to our area

- Causes harm to the environment, the economy, and/or society

Invasive plants cause harm when they:

- Take over garden beds, crowding out valued perennials

- Escape into natural areas, crowding out native plants and reducing food and habitat available to bees, butterflies, other insects, and birds and other wildlife

- Reduce insect populations—for example, invasive trap plants can lure butterflies to lay their eggs on the invasive rather than the true host plant that the hatching caterpillars need to survive

- Prevent the next generation of trees from growing

- Reduce abundance of wild food like mushrooms and berries

- Affect hiking and hunting by forming thickets that are difficult to walk through—in some cases, they retain green leaves long into the fall, impairing visibility

- Take over shoreline areas, affecting boating and other recreational activities, reducing habitat for aquatic creatures, and increasing the risk of flooding nearby homes

- Cause individuals, municipalities, parks, farmers, etc. to incur significant management costs

- Affect human health, for example, through toxic sap (giant hogweed) or berries (bittersweet nightshade)

For example:

- Environmental harm: The crowns of invasive Norway maple trees are ecological dead ends: Birds fly in and then fly right back out again because there’s nothing for them to eat. Periwinkle, lily of the valley, goutweed, and yellow archangel are all invasive groundcovers that can crowd out all native understory plants, completely disrupting the ecosystem.

- Economic harm: Japanese knotweed can cause economic harm by growing through pavement and into foundations. European common reed/phragmites can completely cover shoreline areas, making navigation impossible and affecting fishing. Canada thistle can run rampant on farms and be costly for farmers to control.

- Societal harm: Japanese barberry creates an environment in which the ticks that carry Lyme disease thrive. The sap of giant hogweed and wild parsnip can harm your health by burning your skin—the sap of the former can even cause blindness! And the bright-red berries of bittersweet nightshade are tempting to children but very toxic.

Click here for a list of invasive garden plants

“Why remove invasive plants?”

Because doing so will help prevent harm to our natural areas, our wildlife, our economy, and ourselves. It’s the right thing to do!

Keep in mind that in many part of southern Ontario, invasive plants are wreaking havoc. We are in better shape here in the Sault/Algoma, but invasive plants are making inroads here, too. If you walk into any natural area in the Sault, you will see a boatload of invasive plant species. It’s less costly to stop the problem now rather than letting it become as widespread as it is down south.

“But I can control my invasive garden plants!”

This is magical thinking. Invasive species will outfox us. Their seeds can be carried by wind, water, muddy feet/paws, bird and other wildlife poop. Roots can creep under fences and across property lines. Plus you won’t always own your property. The next owners may know nothing about invasive species and give away or sell ones you left behind.

It’s just not necessary to own invasive plants. You can choose from dozens of native/non-invasive alternatives. It’s possible to have a spectacular garden with zero invasive species in it. Check out our Sault/Algoma Grow Me Instead Guide.

If we who garden love nature (as most if not all gardeners say they do), then we should strive to have minimal impact on ecosystems and the creatures that depend on them.

Take the Gardener’s Oath: “I will do no harm to ecosystems or people.”

“How can I tackle leafy invaders on my property?”

Note: If you have Japanese knotweed on your property, please read this post before attempting to control it. And take special care with garlic mustard—we recommend you follow the Invasive Species Centre guidelines here.

Removing invasive plants can range from simple and easy to complicated, expensive, and time consuming. It depends on what plant species it is, what that species’ quirks and characteristics are, how large the plant is, and how long it’s been growing in that location.

Given how many invasive plants there are, it’s a challenge to provide detailed information on best methods for each. If you are not careful, you can intentionally do more harm than good. For example, trying to dig out Japanese knotweed can stimulate this species’ incredibly persistent root system to grow out laterally many feet!

Below are some ways you can help reduce harm from invasive plants (again, depending on best practices for a given species (check out Ontario Invasive Plant Council guides):

- Before you buy/accept a new plant, confirm it’s not invasive

- Keep in mind that garden centres can still legally sell many invasive plants and staff may not know which are invasive—confirm invasive status via at least two reliable online sources (start with our invasive plants list)

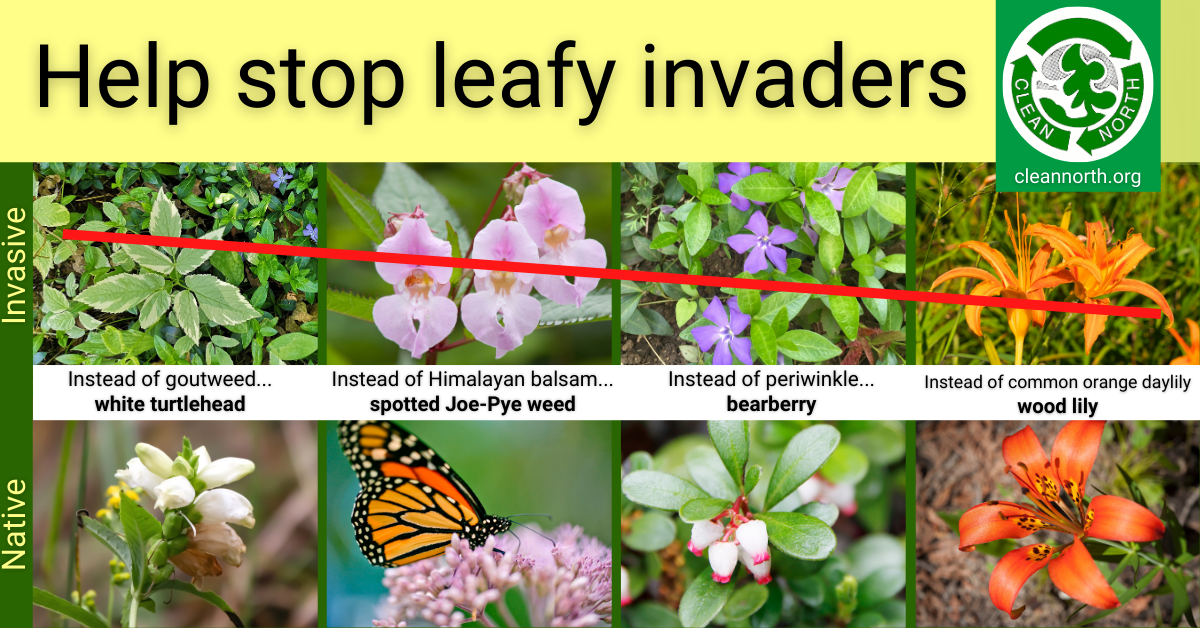

- Be wary of plants marketed as “jeepers creepers” or “vigorous ground covers” (goutweed, periwinkle, creeping Jennie, English ivy, carpet bugle, etc.)—often invasive species

- Grow more native plants (scroll down for where to get them)

- Inventory plants in your yard, find out which are invasive, and make a plan to remove them, again relying on best practices for each species

- Consider starting with the highest risk species/worst infestation, but if you have limited resources, attacking a smaller patch/easier-to-remove species might be a good place for a newbie to start

- Consider these removal/control options but again, confirm best practices for each species:

- Dig up the entire plant (try to get every piece of root), seal it in a heavy-duty trash bag, and put in the trash—consider setting the bag in the hot sun for a few weeks to “cook” the plant material before putting in the trash

- If it’s a large patch, try cutting all stems at ground level, repeatedly mowing it to stress it (no leaves, no photosynthesis, plant is weakened), and/or covering it with heavy cardboard and a tarp for a year or two to smother it

- If you can’t get at an invasive right away, avoid watering it or cut stems at ground level and put a bin, bucket, or box over it to starve it of light and moisture; you can also dig a trench around it to limit spread by roots (be careful digging under a tree or near other high-value plants or you might damage their roots as well)

- Make sure invasive plants do not flower/go to seed—remove flowers/seedheads, bag them, and throw them in the trash

- Plant other vigorous (ideally native) plants that will fill in the space and prevent the invasive from taking hold again (see list of some alternatives to common invasives below)

- Do not compost invasive plant material, especially roots, flowers, and seedheads

- Never dump plant material in natural areas—not even grass clippings, which may contain seeds/seedheads—this is a prime way invasive plants spread

- Don’t move plants from home to cottage or vice versa—invasive roots/seeds may be hiding in the soil

- Clean boots before and after hiking to avoid moving invasive seeds or plant parts to a new location

- Place ornamental ponds well away from lakes, rivers, and streams (flooding can carry invasive aquatic plants into natural water bodies)

- Never dump aquariums (or fish) outside or in natural water bodies—seal unwanted aquarium plants in a plastic bag and throw in the trash

To help fight invasives on a broader scale, consider becoming a supporter of the Canadian Coalition for Invasive Plant Regulation.

“What about chemical herbicides?”

Most uses of chemical herbicides are illegal in Ontario, including residential cosmetic use. However, your local Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry office may give you a permit to use herbicides on an invasive species that’s illegal to own here (for example, Japanese knotweed). That would not be considered cosmetic use.

Here’s a U.S.-based article that presents alternatives to Roundup (glyphosate), the most commonly used herbicide.

Keep in mind that herbicide alternatives can also kill native plants and even insects. For example, if you try to eradicate invasive species growing in patio cracks using the homemade vinegar/salt/dish soap spray described in the U.S.-based article, the consequences will likely be minimal. But using this concoction on your lawn or in a perennial bed could also kill your grass, native plants, and native insects.

“An invasive species is creeping into my yard from a neighbour’s yard. What can I do?”

A tricky situation! If you have a good relationship with the neighbour, you can try to convince them to either remove the invasive or allow you to remove it. Unfortunately, many people still resist the idea that some plants can cause major harm. If getting the neighbour to act is not feasible, your best bet is a barrier:

- Build a “defensive” row of native/non-invasive plants along your property line to bar invading species. Make sure they are close together so there’s no room for invasives to slip through. In shade, goatsbeard and black cohosh would be good native choices. In sun, try wild or spotted beebalm, Joe-Pye weed, swamp milkweed, oxeye sunflowers, coneflowers, and/or blue flag iris. Native shrubs are another option—so many choices! Prefer easy-to-find non-native plants? In shade, hostas, bleeding heart, ligularia, and coral bells are vigorous but not invasive. In sun, daylily cultivars (not the common orange ones—they are invasive!), peonies, Siberian irises, and giant phlox are some options.

- Dig a trench along the property line to limit root spread. You can also dig a trench and then insert/bury flat rocks on end in a row along the property line to act as a barrier. We don’t recommend burying anything plastic in the ground to avoid contaminating soil with microplastics and leaching chemicals.

Click here for a list of plants considered invasive in Ontario

Click here for the Sault/Algoma Grow Me Instead Guide

“Where can I get native plants?”

- Garden centres sometimes carry native plants—before buying, always doublecheck native status via a reliable online source. And keep in mind that nativars (cultivated varieties of native plants) tend to be less useful to pollinators.

- You can also order from online sellers such as Ontario Native Plants or try growing from seed from outfits like Northern Wildflowers (check out our post on growing your own native plants through wintersowing). Here is a list of Ontario native plant sellers but most are in southern Ontario.

How to choose what native plants to grow

“Are all non-native plants bad?”

We encourage growing native plants because they best support our pollinators and other wildlife. But many non-natives do no harm.

Google before buying. Not all garden centre staff are knowledgeable about which plants are invasive. Some garden centres are still selling invasive species like goutweed, periwinkle, Japanese barberry, and Norway maple.

Partners in/supporters of the Clean North Invasive Plant Species Education Project

- Sault Naturalists (especially Valerie Walker and Peter Burtch)

- Kensington Conservancy

- Sault College School of Natural Environment

- Sault Ste. Marie Region Conservation Authority

- City of Sault Ste. Marie

- Lake Superior Watershed Conservancy

- Bruce Station, St. Joseph Island, and Sault Ste. Marie horticultural societies

- Seedy Saturday Algoma

- Algoma Master Gardeners

- Johnson Farmers Market

Special thanks to the Invasive Species Centre and to the Bruce Station Horticultural Society for providing funding for our work.

Want to know more?

Contact us at info@cleannorth.org.

Learn about the link between invasive Japanese barberry and Lyme disease